In one coastal community in southern Haiti, many parents struggled to feed their children and send them to school before sponsors began supporting them three years ago.

Jayson and his family live in a small fishing village off the southern coast of Haiti. His dad works as a fisherman, and every day, he nets his catch in the sparkling, azure blue waters of the Caribbean Sea. What he catches, he sells.

But he almost never brings home any fish for his family.

Instead, they eat spaghetti. Or corn. Or rice imported from the U.S. Some days, they eat almost nothing.

“Fish is expensive,” explains Gustave Richard, a Holt social worker who works closely with families in sponsorship. “If they have it, they’d rather sell it.”

In Haiti, the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, food in general is expensive. Although historically a lush agricultural country that provided ample food for its people, generation after generation of colonial and authoritarian leaders have exploited and mismanaged Haiti’s resources — depleting its soil, and causing rampant deforestation that has worsened the impact of the hurricanes and other natural disasters to which this island nation is already prone. In turn, these disasters have devastated the country’s farmland, as well as the infrastructure needed to store and transport food.

In the coastal community where Jayson and his family live, the impact of natural disasters like 2016’s Hurricane Matthew can be felt in the homes and lives of just about every family that lives here. Dry, barren fields stretch for miles up into the mountains that overlook the sea. Farmers are out of work, and fisherman have no way to safely transport their catch to Port au Prince. Instead, they sell what they can in the local market.

But few families can afford to buy it.

“The community is very vulnerable,” explains Gustave. “There are no plants, nothing to cultivate to eat … Parents can’t afford food for their kids. Some of them only eat when they come here. I know this for sure.”

“The community is very vulnerable. There are no plants, nothing to cultivate to eat … Parents can’t afford food for their kids. Some of them only eat when they come here. I know this for sure.”

Gustave Richard, Holt social worker in Haiti

As Gustave speaks, he stands on the grounds of Fontana Village School – a primary school that sponsors and donors support for the children of this community. A one-room schoolhouse that doubles as a church, Fontana School provides an education for over 100 children, many of whom would never otherwise have access to a school. Many of them live up in the mountains and make the 6 to 9-mile trek on foot to school each day — a considerably shorter distance than the next-closest school. About fifty of them live in the crèche — or orphanage — that shares the same property.

The school opened a little over three years ago, and because of the generosity of sponsors, parents pay no tuition for their children to attend. Already, there’s a waiting list.

“Before this program, certain kids in the neighborhood didn’t have a school to go to,” explains Beverly Sanon, Holt’s representative and program leader in Haiti. “Not only because they are too small or the school was too far for them to walk to, but because the family couldn’t afford for them to go to school.”

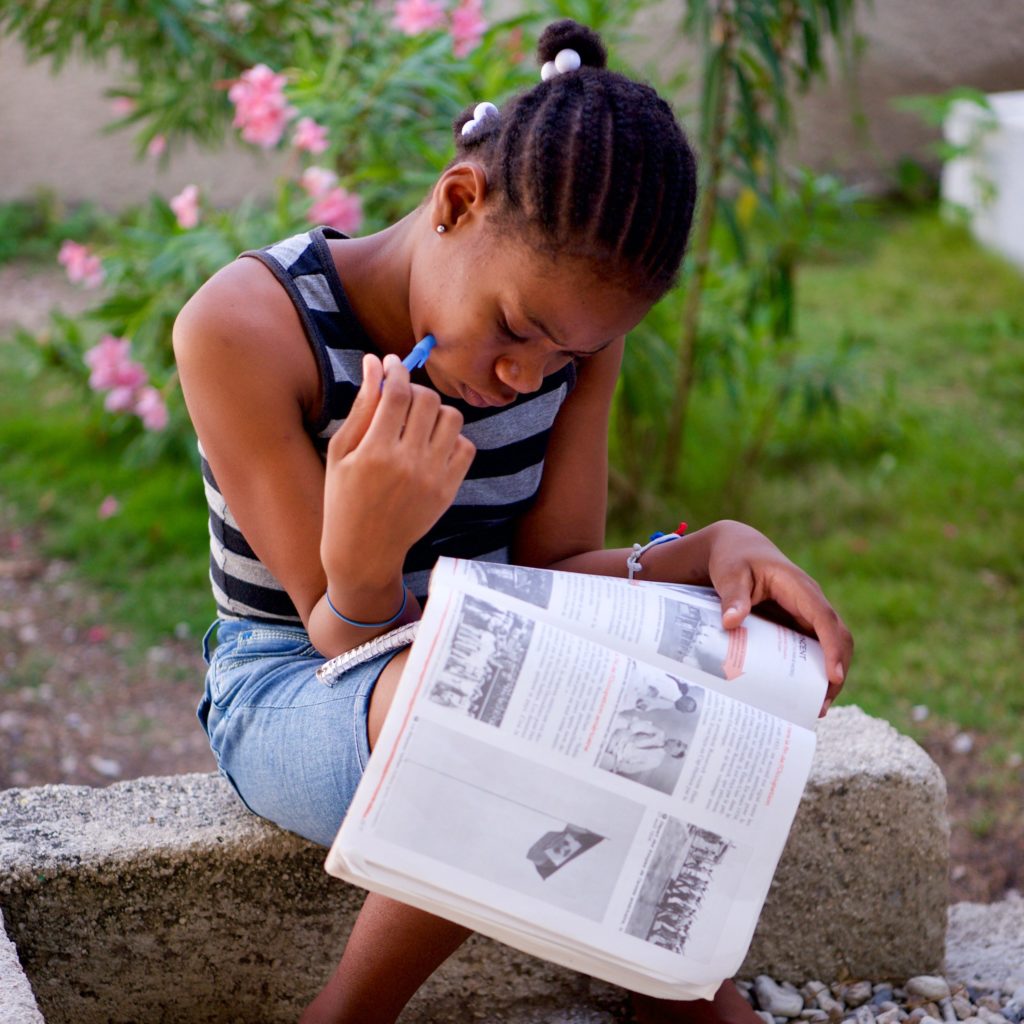

At Fontana school, children ages 3 to 15 learn to read and write. They learn math and science and social studies. They study French and, on the weekends, they have music lessons. Through their monthly gifts, sponsors cover the cost of their books and supplies and uniforms. But the children could not learn a thing if not for the nourishing, protein-rich lunch that sponsors and donors provide for them every day.

That, Gustave and Beverly know for sure.

“Many children don’t eat before coming to school and the teacher can tell because sometimes, when they come, they sleep,” explains Beverly. “The children are very lethargic. Thanks to the lunch that they get, which is made from the staple food — corn or rice — and meat, some protein, and treated water, probably this is the only meal they would have for the whole day.”

When we visit Fontana Village School, on a scorching hot Thursday in late May, it’s just after lunch and the kindergarteners sit patiently in little plastic chairs around a table in the middle of the stone schoolhouse. The older children peek from open-door classrooms. Dressed in neat blue and yellow uniforms, the girls in braids and bows and little white socks, the children stack blocks or play UNO — quietly waiting for their teacher to give them permission to come play with us. When they get the go-ahead, they come rushing over — all of a sudden bursting with the energy and joy and giggles that they restrained a moment ago.

These children are not lethargic. Clearly, something has changed in them since they started eating lunch every day at school.

In the mass of kids, one young man reaches up to shake our hands. He is about 4, and has a smile so big and wonderful that his upper lip disappears and his nostrils flare with giggles and silliness. This is Jayson, whose father is a fisherman.

Jayson lives not up in the mountains like many of his classmates, but in the community just beyond the walls of the school. His home is a short walk to school and a short walk to the beach, set back amid the tropical jungle-like surroundings that is his backyard and playground. In many ways, it’s a natural paradise. But the natural beauty of the environment stands in sharp contrast to the conditions in which Jayson and his family live.

After school, Jayson hurries home to change out of his uniform and into a tank top and shorts. Home is a two-room stone shack with cracked walls and a rusting tin roof and door. It’s stifling hot inside the cramped space that Jayson shares with his parents and five siblings. They have no electricity, no running water. At night, all eight of them sleep under two mosquito nets. Thankfully, none of the children have ever contracted malaria.

“The Ministry of Health provided free nets, but I was not aware so I had to buy my own,” says Jayson’s mom, Claudette, when asked about the mosquito nets that hang down over their beds. “My kids have never gotten sick, though.”

Claudette has a laugh like her son – big and wonderful. She sits down on a wooden folding chair out in front of her home as her youngest son climbs in her lap. She pulls Jayson close. Jayson’s older brother and sister stand in the background.

“When the school opened, I was very happy,” she tells us. “The other school was too far and we needed money for the taxi and for nutrition. And now, it’s free.”

Three of her children now attend Fontana school, and all of her children — except the littlest in her lap — can read, she says. She tells us she’s excited about what her children are learning at school, but the lunch program in particular has made a dramatic difference in their lives.

“It’s very important because sometimes, in the morning, we don’t have anything to feed the children,” she says. “But we know at Fontana, they will get food.”

Jayson shyly buries his face in his hands and turns to his mom when we ask him questions. His older sister Claudia also attends Fontana school, and she stands quietly — poised and confident — with her arms folded. She is 14 and in the 6th grade.

“I like the school,” she says. “I feel comfortable studying there. They are very nice to me, and the teachers are good.”

She tells us her favorite subject is math, and that in her free time she still likes playing with dolls — though she doesn’t have one of her own. It’s her last year at Fontana school, and next year, she will have to transfer to a different school to continue on to 7th grade. Before sponsors began supporting her family, she would have most likely dropped out after 6th grade. But now, because sponsors are supporting her younger siblings, Claudia’s parents can afford tuition for her to continue her education at a traditional public school.

“I’m thankful to my sponsor,” Claudia says, her tone serious and direct. “It’s because of my sponsors that I can go to school. It’s because my mother does not have money to pay the school … I say big thanks for that.”

Claudia would like to be a teacher someday. And even though she faces serious obstacles, this is an attainable goal – that is, if she can stay in school.

“We have an issue with dropouts in Haiti,” explains Beverly, who grew up in Haiti but worked for years as a teacher in New York City after moving there in the mid-1980s to earn her master’s degree in education and social work. Beverly is quick to emphasize that Haiti’s high dropout rate is primarily because of financial barriers — and not due to poor performance or lack of dedication on the part of the children.

Beverly also taught junior high school in Haiti for a number of years, and the difference, she says, is striking.

“In New York City public schools, you have to be a security guard, a social worker, a mother, a father. You have to be so many things before you can teach,” she says.

Beverly recognizes that kids living in inner city New York face a lot of challenges at home and in their communities. But in Haiti, eighty percent of children attend private schools because there are so few public schools. Often, she says, parents who can’t afford private school will bribe the directors of public schools to secure a place for their child.

“In New York City, kids know, ‘I will have a school to go to no matter what.’ But here,” she says, “they know their parents have to pay for it so they want to get the most out of it.”

“In New York City, kids know, ‘I will have a school to go to no matter what.’ But here, they know their parents have to pay for it so they want to get the most out of it.”

Beverly Sanon, Holt’s in-country Haiti director

And that is not the only difference between education in Haiti and education in the U.S.

In Haiti, the gender divide is still very real — especially in impoverished rural communities like the one where Claudette and her family live.

“[Parents] will often send their smartest child or the boy because later, the boy has a better chance of helping the family” Beverly says, explaining how many parents decide which of their children to send to school. “Whereas the girl has to learn cooking and learn from the mother.”

Parents push the boys, Beverly says, because they tend to earn more in trades traditionally done by men. But the gender gap is beginning to close, especially in communities supported by sponsors.

Because sponsors help pay for tuition, books, supplies and uniforms with their monthly gifts, Claudette doesn’t have to choose which of her six children to send to school. She doesn’t have to choose between buying food and paying school fees. Jayson can go to kindergarten and Claudia can pursue her dream of becoming a teacher.

Before sponsors stepped up to help her family, Claudette worried how her daughter would continue her education. She supports her daughter’s dream, and has dreams for all of her children.

“I’d like all my children to become very educated people to help Haiti,” Claudette says. “Sponsors have helped me so much.”

“I’d like all my children to become very educated people to help Haiti. Sponsors have helped me so much.”

Claudette, mother of a sponsored child

More importantly, sponsors have helped her children and all of the children at Fontana Village School. She sees the need in her community and hopes that the school can expand and offer a free education to many more children.

Already, in three short years, sponsors and donors have created a miraculous change in the health, the vitality, the happiness and the hopefulness of the children they support. They have changed their lives.

Claudette sees it. Gustave sees it. Beverly sees it. And every time they do, they think of the generous and warm-hearted people who made it possible.

“Sponsors, donors, we know that you have found it in your heart to help these children. You have been great,” Beverly says. “Not because you have more than you need, but because you think it’s a duty to share with others. And these kids really appreciate it. When you see their level of activities, when you see their joy, when you see them singing, when you see them playing the flute, it’s a joy. And we thank you every time we look at them.”

Send a Child to School

The gift of a scholarship covers tuition for one student to go to school for one year.