The children of migrant families are some of the most vulnerable in India, and they are often excluded from schools and at risk of exploitation, trafficking and abuse. Recognizing the needs of this growing population, Holt’s partner in the region completely refocuses their efforts, using education as a transformative tool.

Avni pulls her husband and son’s stiff, sun-dried pants and shirts off the frame of wooden scaffolding built outside her home. She climbs the seven unfinished concrete stairs, and drifts through the wide, cement hole where a double door and massive picture windows will someday lead into the lobby of a six-story apartment building. But, at that point, her family won’t live here anymore. It will be time for them to move on in search of another job, and another home.

Avni is 26 years old, and the mother of three children — an 11-year-old daughter and two sons, Basha, 9, and Mapasha, 6. She is strikingly beautiful, and has a kind, shy smile that peeks through the whole time she speaks, the little ring in her nose glistening. Her feet are bare under her purple sari, except for a thin, gold toe ring, which married women commonly wear in India as a token of luck in marriage.

Avni and her family migrated from their rural village to Bangalore, India six years ago for work, hopeful that they could find better jobs and make a better life for themselves and their children.

They weren’t the only ones.

A booming metropolis, Bangalore — the unofficial tech capital of India — is growing at an unprecedented rate. Sprawling and vast, Bangalore is marked my miles upon miles of towering buildings, new development and urbanization. On nearly every street, evidence of growth is visible in the empty frames of partially complete apartment complexes, high-rise buildings and smaller, commercial businesses.

And while the plentiful jobs that new development brings is good news overall, some of the effects of rapid urbanization and mass migration are less pretty — particularly on the children of migrant workers.

In the shadow of nearly every new building is a tent city — a temporary neighborhood built from tarps and scrap materials, often without plumbing or electricity, where entire migrant families will live for the 2-4 years they are employed to build.

Migrant families and children, like Avini, Basha and Mapasha, are some of the most vulnerable in India. They come from the poorest regions, are often uneducated or illiterate, and tend to be a part of lower castes. If they also happen to have darker skin, it can make them even more of a target for discrimination. Because of these factors, migrant families have very little ability to change their economic situation. It’s unlikely that hard work alone will enable them to achieve lasting stability or build a substantial savings. Employers pay them the lowest wages. Schools discriminate against the children, and prevent them from attending. If they are the victims of a serious crime, they are unlikely to report it because they know that police are unlikely to punish a perpetrator from a higher class — or even bother investigating the crime. There is very little social welfare, so families are unlikely to receive nutritional aid, medical care or family assistance from the government.

Mary Paul is the director of Vathsalya Charitable Trust, Holt’s long-time partner organization in Bangalore. She has lived and worked in this region most of her life, finding creative and innovative ways to care for orphaned and vulnerable children, and provide struggling families from impoverished communities with the support and services they need to grow strong, stable and self-sufficient.

Several years ago, Mary Paul began to notice an influx of children from migrant families right in her own neighborhood. “We would look around at all the building projects and see kids just laying around,” she says.

There is no clear estimate for the number of migrant children in India. In Bangalore, best estimates place that population around 15,000 — however, nearly everyone agrees that this estimate is probably much too low.

Children of migrant families are extremely vulnerable to abuse, exploitation, trafficking and child labor violations. They often spend their days alone and unsupervised in the unsafe conditions of the construction sites. They may not have enough to eat, and very few attend school. Throughout India, more than 11.9 million children aren’t in school — often due to poverty, discrimination or family instability. Children of migrant worker families face even greater barriers to education. In addition to the cost of tuition, many schools will not admit students from migrant families, knowing they may leave at any time.

Recognizing this growing need among children of migrant families in Bangalore, Mary Paul soon came up with an idea of how to help them. “I would think ‘we should open a daycare so these children can get an education and be taken care of during the day,’” she says of every time she passed another construction site full of children.

Two years ago, VCT shifted focus — moving away from adoption, and toward programs aimed at keeping some of India’s most vulnerable and at-risk children and families together, and in particular those who had migrated for work. VCT first opened a daycare in 2014 so children from migrant families wouldn’t be alone during the day. The daycare grew into an informal school, and now a formal school.

One of the first families they met after opening the daycare was Avni’s.

Avni never had the opportunity to attend school as a child. She is illiterate, but she speaks slowly and confidently. Her husband completed the first grade. Avni had her first child shortly after her parents arranged her marriage when she was barely 15. When her husband decided to travel from Andhra Pradesh to Bangalore in search of work, Avni was left with a difficult decision. Traditionally, orthodox Muslim women don’t leave their homes, but Avni was intent that she would not be separated from her husband and sons. However, her decision to migrate with her husband was not without sacrifice. She had to leave her daughter behind.

Upon arriving in Bangalore, Avni and her husband quickly found jobs. They met a man who hired Avni and her husband to build a six-story apartment building. Kind and caring, the employer allowed Avni and her family to live on the first floor of the building rent free, at least while the space is unfinished. He also pays Avni for helping her husband build, and encourages her to keep her sons in school. However, the standard of living is somewhat shocking, even in India.

The bottom floor of the building where Avni lives is large and open, with a few electric light bulbs hanging from hung cords and wires. Stacks of wood and bricks and crates of materials and tools litter the room. The floor is dusty, unfinished concrete, and the framed-but-unfilled windows fill the space with light in the day — but leave the family completely exposed to weather and intruders at night. In the back corner, a small room without windows is framed by bricks, with a small, blue door where Avni, her husband and their children sleep. Inside, the room is packed with scraps of wood, building materials and a small, single-sized mat with a few crumpled blankets. At first look, it’s hard to distinguish where everyone would even fit to lie down, and there is no ventilation or even a window. Outside the room along one wall, Avni built a small fireplace out of three or four bricks, and she builds a wood fire to cook meals for her family. She also built a couple of small shelves, where she stores some recycled plastic bottles with spices and pickled food, a few pots and pans and one plastic water jug. They have electricity, but no running water or toilet.

But Avni says she is happy. Basha and Mapasha attend VCT’s daycare program and for the first time are receiving an education. This is opening new doors for the boys, and transforming the way Avni views education. It’s also keeping the children safe.

Education is extremely powerful in India, helping children overcome barriers related to class, race, gender and caste. If a girl from a poor family is able to stay in school, it is truly the best chance she has to create greater stability for herself, find a better job, and raise healthy children. When a girl is educated, she also recognizes the value of education — and will go above and beyond to ensure her children are also educated. Through education, children have the power to break the cycle of poverty forever. But sadly, school isn’t free, and the cost of tuition and supplies is often out of reach for the families VCT serves.

Tuition is only about Rs. 6,000 rupees per year for a child to attend VCT’s school, or about $100 U.S., and almost every child has their tuition waved thanks to sponsors and donors through Holt. However, the average middle class, college-educated person in Bangalore may make around $300 U.S. per month. Housing costs, food costs and more are all extremely high, with rent prices soaring nearly as high as costs in some of the cheaper regions of the U.S. Even for parents with education and good jobs, extra income is tight. For struggling families, those in lower castes, those in impoverished communities or those who are illiterate, they may make less than $1.25 per day — putting the cost of tuition entirely out of reach for their children.

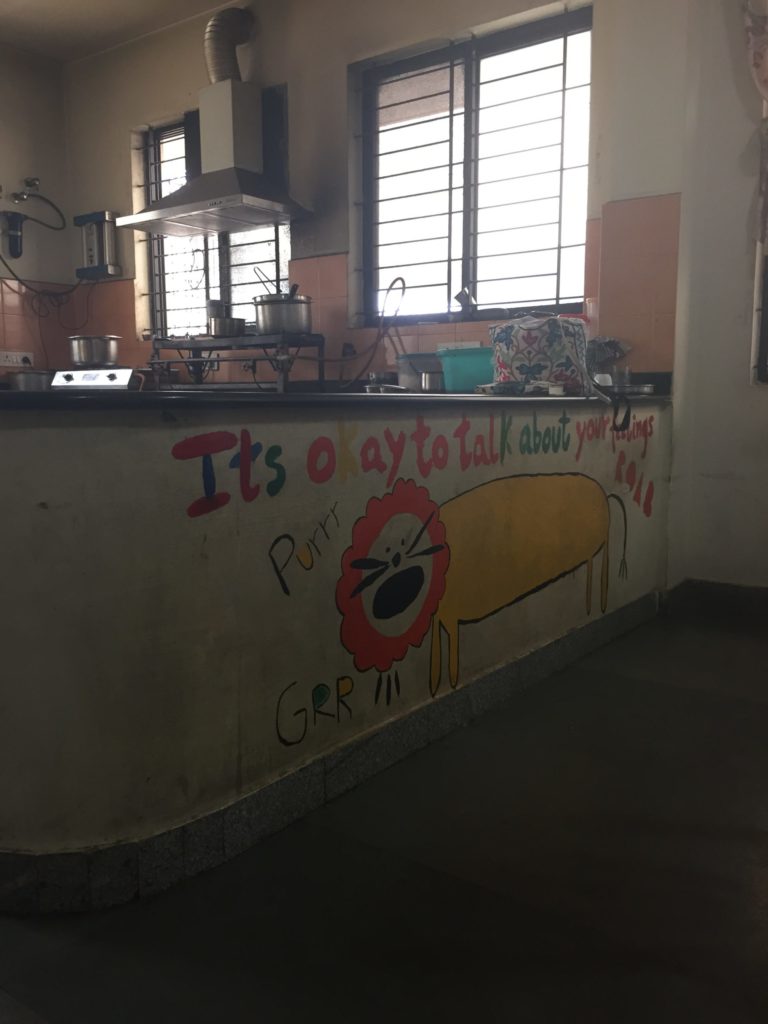

The VCT staff — a team of strong, educated female teachers, social workers and aids — do far more than just run a school. They also visit the homes of each child and regularly check in with the families, helping them set goals for the future and access any resources they need to grow more stable and healthy.

The school provides daily meals and, if they need to, medical care when children fall ill. They offer educational courses to parents in the evenings, on top of all their other programs — including partnering with 17 schools across the state to find sponsors for girls and working in rural northern villages to provide health training courses and basic medical care. And most recently, they’ve taken a renewed focus on nutrition with the help of Holt.

In 2013, Holt began an ambitious initiative, aimed at completely revolutionizing the way we approach nutrition and feeding for orphaned and vulnerable children. We partnered with Portland, Oregon-based non-profit SPOON Foundation and together, we retrained caregivers, school teachers and social workers in four countries about child nutrition, tracking children’s health and growth, feeding techniques and more. VCT was one partner program excited to receive the training — and to implement it widely. Initially intended for orphaned and abandoned children living at VCT, we soon realized the program would benefit children at the daycare and informal school, significantly cutting back the rates of malnutrition — the largest killer of children under 5 — as well as anemia, which stunts children’s brain growth and development. Since implementing the Orphan Nutrition Program (ONP) for children in VCT’s daycare program, the children’s health has improved significantly. They’ve seen children’s energy level rise, as well as their ability to actively engage and retain school lessons.

“We’ve seen a growth spurt in children in the last six months,” says VCT’s educational coordinator, Joyce Ranjan. “This includes children in our program for migrant families. The parents are so thankful. They want the trainings to continue.”

For children of migrant families, education about nutrition is especially critical to the health and safety of the family.

Parents who have migrated for work often take extremely demanding jobs, both in terms of the physical output and the number of hours worked. They are busy and exhausted. Before school or after work, cooking is another time-consuming and work-intensive task, since most meal preparation is done over a small, open fire where parents squat and hunch to prepare rice or popular tortilla-like chapatis. Rather than expend the time and energy to cook, many parents would give their child a few rupees to purchase chips or cake from the bakery. While these foods would fill the child’s belly, he or she wouldn’t get any nourishment, and would eventually grow malnourished.

“We tell parents to spend their money on fruits and milk,” Joyce says. “Parents come to VCT once per month on Sunday for trainings, and we talk a lot about what children should eat.”

In India, especially in impoverished communities, it’s not uncommon for parents to give even toddler-aged children coffee and tea instead of milk, thinking it’s a cheaper alternative and not understanding the critical nutrition that milk provides. These types of feeding misconceptions are common, but easy to dispel.

“Parents want to do the right thing,” Joyce says. “But often, no one has taught them what is the best. They’ve learned from the way their mothers did things.”

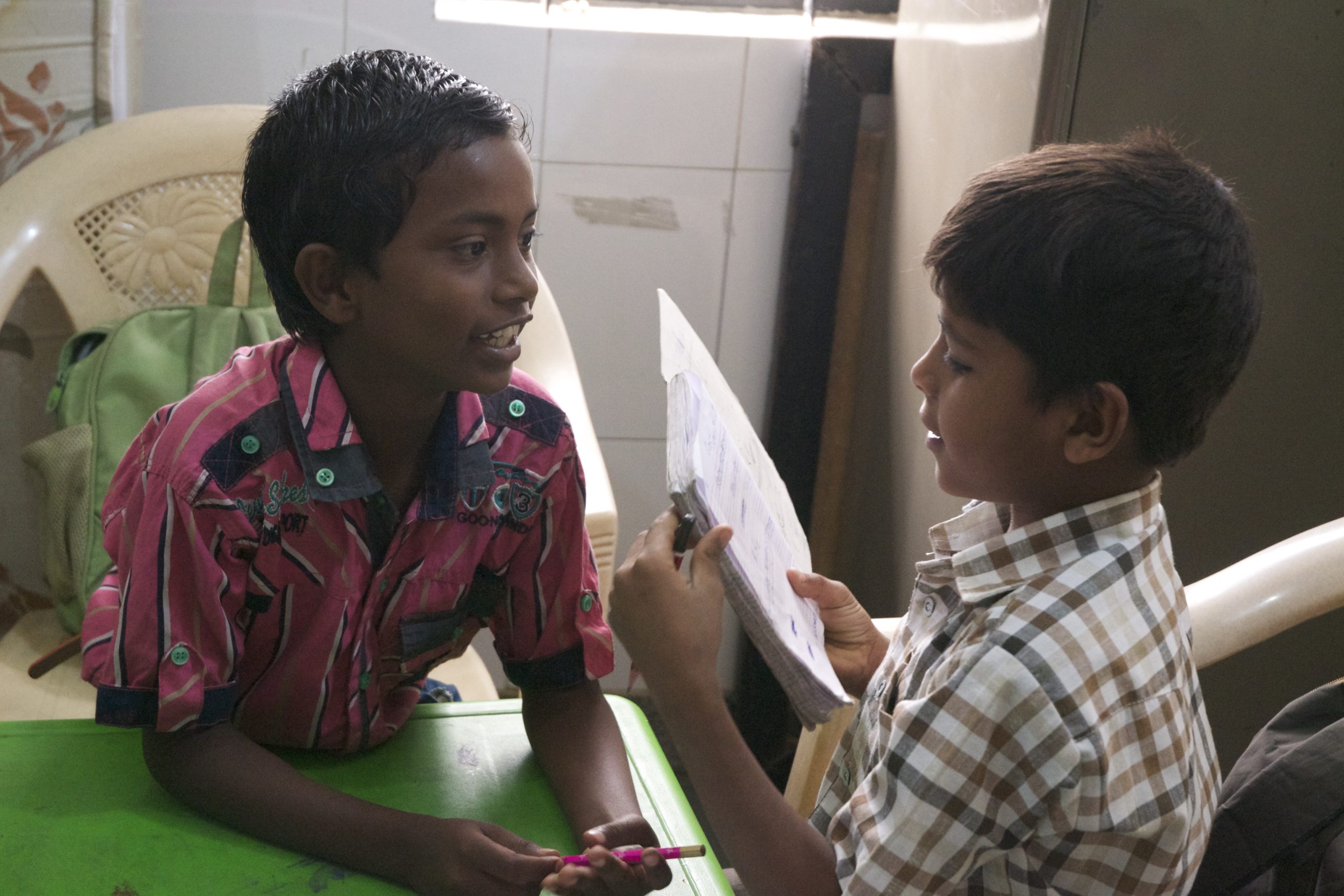

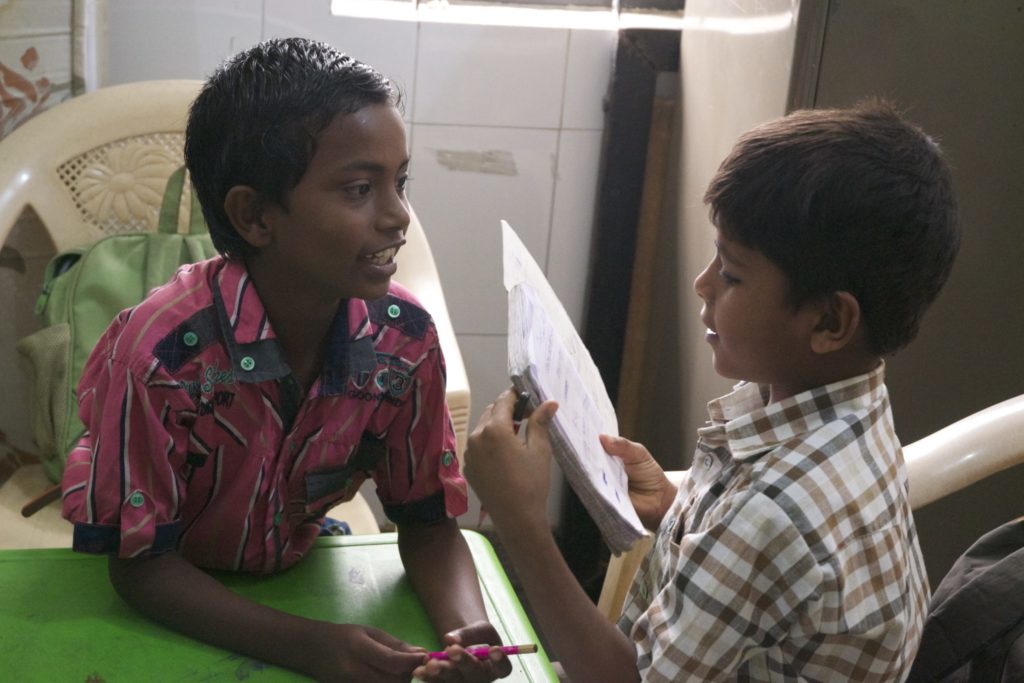

For all children in their programs, VCT takes photos of the children to track their physical growth and update sponsors. Here are Basha and Mapasha’s before and after photos from the past year. VCT staff and Avni, Basha and Mapasha’s mother, said they have seen a growth spurt in the children since starting Holt’s orphan nutrition initiative in 2013. VCT also tracks rates of anemia and iron absorption, hemoglobin, and more.

For all children in their programs, VCT takes photos of the children to track their physical growth and update sponsors. Here are Basha and Mapasha’s before and after photos from the past year. VCT staff and Avni, Basha and Mapasha’s mother, said they have seen a growth spurt in the children since starting Holt’s orphan nutrition initiative in 2013. VCT also tracks rates of anemia and iron absorption, hemoglobin, and more.Even for adults, the education they receive at VCT is transformative. Most of the parents whose children attend the migrant school are illiterate or have very little education. When an adult can’t read or write, they also struggle to protect themselves from abuse or exploitation, and fearing that they may not have the knowledge to file a police report or argue their case, many uneducated adults are unlikely to report even the most serious of crimes. Furthermore, their job opportunities are limited and their pay dictated by their employer.

VCT has a strong community and parent education program, with a simple premise. Rather than hold onto wisdom — like what they learned during nutrition training through the ONP — they pass it on to parents, who pass the same learnings onto their children. This is especially important for women and mothers, who Mary Paul says hold the keys to massive community transformation and growth. By educating women and mothers, they also fight gender inequality, which is pervasive in India.

“When you educate a girl, you educate a generation,” Mary Paul says. “What happens here is a woman really has more influence over her children, and what we found is that if you educate a man, he will hold his knowledge. But an educated mother will see to it that her child is educated — and it doesn’t matter if her child is a boy or a girl. She will want her child in school.”

Female education, and keeping girls in school past puberty, is a critical goal of VCT. Once girls are mature, parents are less likely to send their child to school. Instead, girls are married off or put to work to help bring home income to their family. This strips girls of their ability to reach for their dreams, get better paying jobs that allow them to support their children, and choose when, and if, to marry and start a family of their own. But convincing families to do something different can be challenging.

“We tell mothers that the girls don’t have to be like their mothers,” Joyce says. And, truly, that is a totally new way of thinking. So much of what VCT — and many of our partners around the world — do is empower parents through education. Especially for mothers, who tend to take on most of the responsibility of child rearing, education can truly transform their family and community.

“We have mothers come to the school and say, ‘What’s the point of my daughter going to school? We need money.’ And they pull their daughter from school. We try to fight it. We try to teach the parents, but it doesn’t always work. Even if you go to the police, they will probably just turn their heads. But, we have also seen many mothers change their entire way of thinking and parenting. Now, they tell other mothers about the importance of keeping their girl child in school.”

Joyce Ranjan, educational coordinator at Holt partner VCT

Avni says that as an adult, she doesn’t really have the desire to learn to read and write. However, she is happy that Basha and Mapasha are learning these skills and receiving nutritious meals each day. She says that her children have grown taller and gained weight since they started school. They are healthier now and have more energy, and they hate missing a day at VCT, even if they are sick. Avni says that she has learned a lot about the importance of education from parent meetings at VCT. This prompted her to enroll her daughter, who lives with her grandparents in Andra Pradesh, in a local vernacular school. While Avni still hopes her daughter marries soon after completing her basic education, this kind of transition of thought is exactly what motivates the VCT staff — and why they see women, particularly mothers, as a critically important part of their success formula.

“We have mothers come to the school and say, ‘What’s the point of my daughter going to school? We need money,’” Joyce says. “And they pull their daughter from school. We try to fight it. We try to teach the parents, but it doesn’t always work. Even if you go to the police, they will probably just turn their heads. But, we have also seen many mothers change their entire way of thinking and parenting. Now, they tell other mothers about the importance of keeping their girl child in school.”

So much of a girl’s education is about more than just reading, writing and math. In India, sexual abuse is rampant in girls as young as 3. Especially for children in lower castes or poor families, they have few protections from abuse and fear the stigma and shame that repeatedly victimizes girls, but fails to prosecute men. Often, for a poor or uneducated woman or child, the police will just turn away from the crime. In India, there have even been news stories of police arresting women who report abuse. Many girls don’t even know they are being abused, so VCT trains girls — and boys — how to identify and report abuse. This education is helping to curb abuse and keep children in school.

“My goal is to educate as many girls as possible,” Joyce says.

Bright and quick to learn, both Basha and Mapasha are picking up reading, writing and English speaking skills rapidly. It was this type of student success — seeing the children’s potential — that inspired VCT to grow their program and offer more tools to the students.

Just this year, VCT moved from offering informal education — meaning they couldn’t offer a graduation certificate — to formal education. They plan to grow with their students, adding a new grade level each year so no child ages out of their school. In the short term, this plan will work. However, in the long term, VCT knows that they will eventually outgrow their current space. They are trusting that God will provide a new building sometime in the next five years, so their plan can come to fruition.

Eventually, they want to offer a program that matches students with loving foster families, which would allow children to stay in school even if their family must move away for work for a while. And it would boost the local economy, helping to support even more families. That’s for the future. But for today, the teachers are content as they watch parents pick their children up from school and daycare, excited to hear what their child learned that day. The children speak the English words they learned, and the parents smile and repeat the words out loud. The children and parents hug and smile, and Mary Paul and Joyce smile, too.

Billie Loewen | Former Holt Team Member

Send a Child to School

The gift of a scholarship covers tuition for one student to go to school for one year.