Every year, over 6,000 young adults age out of orphanages in Korea. As “orphans,” they face stigma and discrimination, and have no support or guidance. But one organization is now working to change that — providing love, and hope, beyond the orphanage.

Myung Hoon plays the viola beautifully.

Beautifully enough to win second place in a solo competition with musicians who learned to play the instrument years before he did. Beautifully enough to earn a scholarship to New York’s prestigious Manhattan School of Music. But no matter how beautifully he played, for a long time, Myung Hoon never felt like he was enough. Like he deserved what he achieved.

“I did not have a dream when I was young because I did not grow up in a family. I thought orphans do not deserve to have a dream.”

Myung Hung wrote these words in a letter to Love Beyond the Orphanage (LBTO), a U.S.-based organization that provides scholarships and support for young adults who grew up in orphanages in Korea. Young adults who once they turn 18, find themselves unceremoniously released into society with nothing but a $3,000-$5,000 stipend, and absolutely no survival skills.

According to Julie Duvall, who co-founded LBTO with fellow adoptee Kim Hanson, this is the time in their lives when they are most vulnerable.

“They have no skills. No one to trust. And it is scary,” she says. “A lot of them struggle. It’s a scary world for them.”

“They have no skills. No one to trust. And it is scary. A lot of them struggle. It’s a scary world for them.”

Julie Duvall, co-founder of Love Beyond the Orphanage

Julie especially worries about the girls, who are vulnerable to predators and sex traffickers who prey on young women without any family ties. Some aged-out orphans end up turning to crime as a means of survival. But in most cases, they simply struggle to get by in a society that shames them at every turn for something they have absolutely no control over.

They are orphans. And in Korea, orphans do not deserve to dream.

“It’s just very unfair for them – for orphans,” says Julie. “In Korea, bloodline is very significant. If you don’t have the bloodline, they don’t look at you the same.”

Although Julie uses the term “orphan,” the irony is that most children growing up in — and aging out of — orphanages in Korea are not actually orphans. They have a family. They have parents. The reason most children end up in orphanages in Korea also has nothing to do with poverty, as in many countries. Rather, it has everything to do with the overarching cultural value placed on a “pure bloodline.” These “orphans” are the children of single mothers — women who, had they chosen to parent, would face the same stigma, discrimination and shame that their children now face as they age out of orphanages and enter Korean society. Having a child out of wedlock breaks a family’s bloodline. But being an orphan means you have no bloodline. You don’t belong.

Over the past 70 years, over one million children have grown up in orphanages in Korea, with 6,000 young adults aging out every year. And since August 2012, when the government passed a law that makes it harder for children to be adopted, Korea’s population of orphans has only continued to grow.

“Now that adoption is declining, that means more babies are sent to orphanages. That means more babies are going to grow up and age out,” Julie says.

But even in Korea, Julie says, many people have little to no awareness about the growing crisis in their country.

“The public has no idea that orphanages even exist in Korea. Some people may know, but [they don’t know that] several thousand orphans are aging out,” she says. “One orphanage we visited has 600 orphans. It’s unthinkable! And no one knows.”

Through Love Beyond the Orphanage, Julie Duvall and Kim Hanson are determined to make people know about the crisis of aged-out orphans in Korea. Both Korean adoptees, Julie and Kim have a unique heart and passion for the children left behind — the ones who weren’t adopted. But Julie in particular shares a special bond with aged-out orphans in Korea. Adopted as a young adult, Julie’s story is unusual. She lived in an orphanage until she turned 16, and never expected to join an adoptive family.

Like the kids she now advocates for, Julie was also an aged-out orphan. She was one of them.

Julie wears glasses, a little silver cross around her neck and a brace on her wrist from a tennis injury. After 30 years in the U.S., she still speaks with a bit of an accent, which she’s self-conscious about, and she insists she’s actually very shy. But when she talks about her life in Korea and the life of aged-out orphans who still live there, her voice is forceful and clear. She does not wait for questions. She does not break for air.

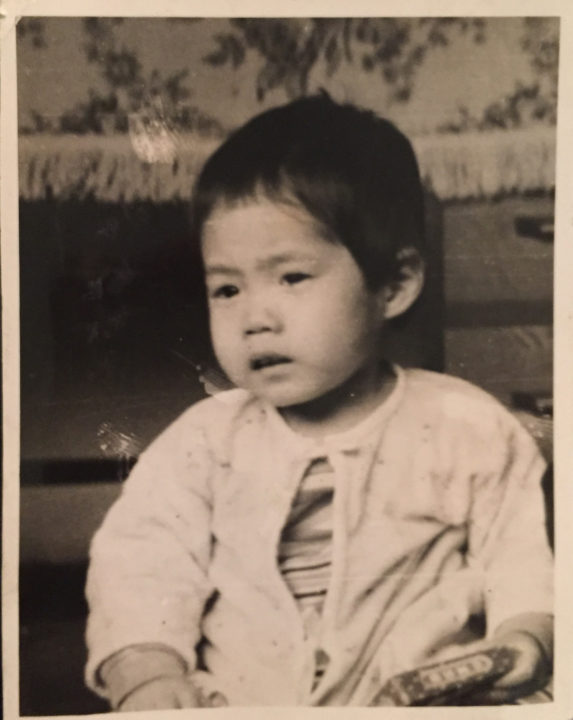

“I grew up in an orphanage in Korea and aged out at age 16 only because back then – in the 1970s and 80s – Korea in general was very poor. Everyone was struggling, and orphanages were struggling even more to support those orphans,” she says. “I remember growing up in the orphanage where food was not there much. It was not a pleasant experience.”

Julie lived in a small orphanage with just 25 other girls. They became her sisters, her family, and together they survived. But she says the 16 years she spent in an orphanage was the darkest period of her life.

“Our orphanage was a private orphanage so we went through so much abuse physically, mentally and sexually,” she says. “I escaped the sexual part, but I have come very close to being one of the victims.”

Today, she says, the Korean government provides more oversight and protection for children living in the country’s social welfare system.

“But when I was growing up, none of that existed … A lot of girls went through the trauma of abuse and still to this day, some of them are suffering,” Julie says of the girls she grew up with — of her “sisters.”

At 16, Julie left her orphanage to serve as a live-in housemaid for a family in her community, which 30 years ago was a common way for aged-out orphans to pay for their high school education. But from day one, they made it clear to Julie that she was not a part of the family. She was there to work, and that’s it.

“In Korea, when you are working for somebody and the owners know that you’re an orphan, how they treat you is a lot different,” she says. “You are their employee, but they really don’t care about you.”

Bloodline and family name are so valued in Korean culture that many aged-out orphans struggle to find jobs in the first place. Even if they overcome the odds and earn a college degree, they will still face discrimination in the hiring process. In Korea, all job applications require a birth certificate or family name.

“They will see that you are an orphan,” Julie says. “That causes them to reject you.”

“They will see that you are an orphan. That causes them to reject you.”

Determined to earn her high school diploma, Julie continued working as a housemaid until she graduated. After that, she found a low-paid job delivering supplies to office buildings. She endured sexual harassment by her supervisor, but never spoke up. She was an orphan, after all. Who would take her seriously?

After six months, she injured her back and quit.

“I had no money, no place to go, no friends. I didn’t have anybody,” she says. “So I ended up visiting Molly Holt at Ilsan.”

The second eldest daughter of Holt founders Harry and Bertha Holt, Molly Holt devoted her entire life to advocating for orphaned and vulnerable children in Korea. From her early 20s until she passed away in her 80s, Molly lived at Ilsan, the long-term care center for children with special needs that her parents founded in the early 1960s. In Molly, Julie found a friend and advocate.

“Molly accepted me. She allowed me to stay with her at her house. She knew my situation,” Julie says.

For a time, Julie lived and worked at Ilsan. But it soon became clear to her that she had no future in Korea. She had no desire to work as a housemother, the only job available to her at Ilsan. Then, one day, she met the Mayberrys, an adoptive family from Eugene, Oregon. They had traveled to Korea with their three adopted daughters, and stopped at Ilsan for a visit. Molly told the Mayberrys about Julie’s background and the difficulties that aged-out orphans face in Korea, and they felt compassion for Julie — and started looking into how they could help her. They reached out to the leadership of Holt International in Eugene, who brainstormed a way for Julie come to the U.S. on a work visa. They even offered for Julie to live with them while she worked at Holt.

That year, the Mayberrys asked Julie if she would like to legally become a part of their family. She said yes.

“Just an amazing family, wonderful people,” Julie says of her adoptive family. “I felt very blessed to have gotten this opportunity … I didn’t expect any of this to happen, but I had faith that deep in my heart, I wanted to come to the U.S. The number one reason, I knew I could work hard — and no one cared whether I was an orphan or not.”

Julie went on to attend college in the U.S., get married and raise two lovely daughters.

“I’ve been blessed,” she says. “I could just enjoy my comfortable life. But I feel that’s not why God brought me here.”

Although Julie had no desire to return to her birth country, she could not stop thinking about her sisters back in Korea.

“It was always in the back of my mind how my sisters are continually suffering,” she says.

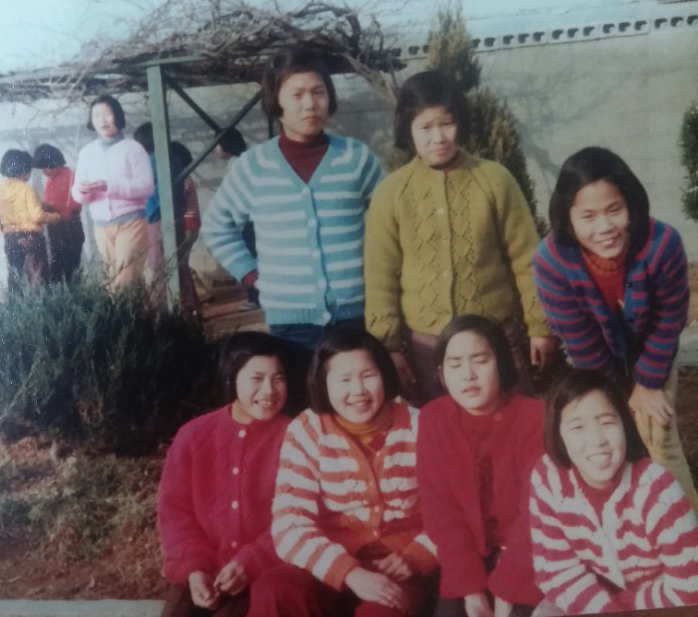

Most of Julie’s sisters found work in factories or in other low-paid jobs — often the only jobs that aged-out orphans can find in Korea. Some of them married, some of them are divorced. Some of them stayed in abusive relationships because they had nowhere else to go.

“But they’re survivors,” Julie says. “They have to work every day, sometimes seven days a week, to provide for their family. But when we’re together, they’re just happy to see each other.”

To advocate for her sisters, Julie became a board member of Korea Gospel Mission, an organization that supports orphans and aged-out orphans in Korea. When her sisters struggle financially, the mission can allocate funds to help them. Every so often, Julie travels to Seoul to visit her sisters as well.

“I could easily say, ‘I am done with my life in Korea,’” she says. “I don’t want to go back and think about it and relive this horrible life in Korea. But there’s something in me that says, ‘These are your sisters.’ So I will go back and be there for them …I want to let them know they’re not forgotten.”

Julie couldn’t forget her sisters in Korea, but she also could not stop thinking about the thousands of other orphans aging out every year into a society that shuns and discriminates against them.

“The reason no one is coming to defend vulnerable orphans is because no one understands their outcome,” she says. “But I went through all that and completely understand what they’re facing. I always felt in my heart that someone has to be their voice. But no one is doing that in Korea … And nothing has changed. Nothing has changed in their attitudes toward orphans.”

Every so often, Julie and Kim would get together with other adoptees, and talk about their lives in Korea, or talk about what they saw in the media. They felt especially emboldened to speak out against the anti-adoption movement in Korea — a movement led primarily by Korean adoptees who grew up in the U.S. and other countries.

“[Adoptees] go to Korea and they advocate against adoption,” Julie says. “Whenever I hear that, it really upsets me because there are so many orphans who did not get chosen to be adopted into a family. And they age out, and they will remain as an orphan for the rest of their lives, live in silence. Those adoptees have no idea … If they were not chosen to be adopted by families, they would not say what they say in Korea. NO way.”

Upset by the very loud and vocal opposition to adoption in Korea, Julie and Kim felt like someone needed to speak up on behalf of orphans — both those who are now aging out into Korean society, and future generations of aged-out orphans who are now growing up with no way to join a family through adoption. That’s when they decided to create LBTO.

“With my story, with my experience, and with Kim Hanson and her adoption experience, we said we need to do something … And so we formed the organization Love Beyond the Orphanage,” Julie says.

Through LBTO, they hoped to bring awareness to the struggles that aged-out orphans face in Korea. They wanted to be their voice, and their advocate. But they also wanted to give them the opportunities and support that they miss out on simply because they don’t have families.

Growing up in an orphanage is, itself, a huge disadvantage for any kid trying to succeed in Korea’s competitive educational system. “They have to work twice as hard to maintain the same grades as non-orphans,” Julie says. “Because they didn’t get to have private lessons. And when you’re living an institutional life, mentally, you’re several years behind the kids who have families.”

To help close the gap, Julie and Kim began raising funds to provide scholarships for a handful of young adults pursuing higher education or vocational training. Although the government will cover the cost of tuition for aged-out orphans to attend college in Korea, the students often struggle to afford the cost of books, transportation and basic living expenses. And as many of them have to work twice as hard to maintain their grades and keep their scholarships, they struggle to hold down jobs that will cover their expenses.

“What we’re doing is helping them stay in school by offering an extra $500 a month for food, transportation, books, have a meeting with their friends, have coffee or go out to dinner,” Julie says. “Other kids have those privileges, but these kids don’t. We want to provide that for college kids so they graduate from college and they’re not struggling to figure out how they’re going to get food the next day.”

But it’s not just material support these kids need. Through LBTO, Julie and Kim want to give aged-out orphans something more than they experienced in the orphanage. They want them to experience what it’s like to be part of a family.

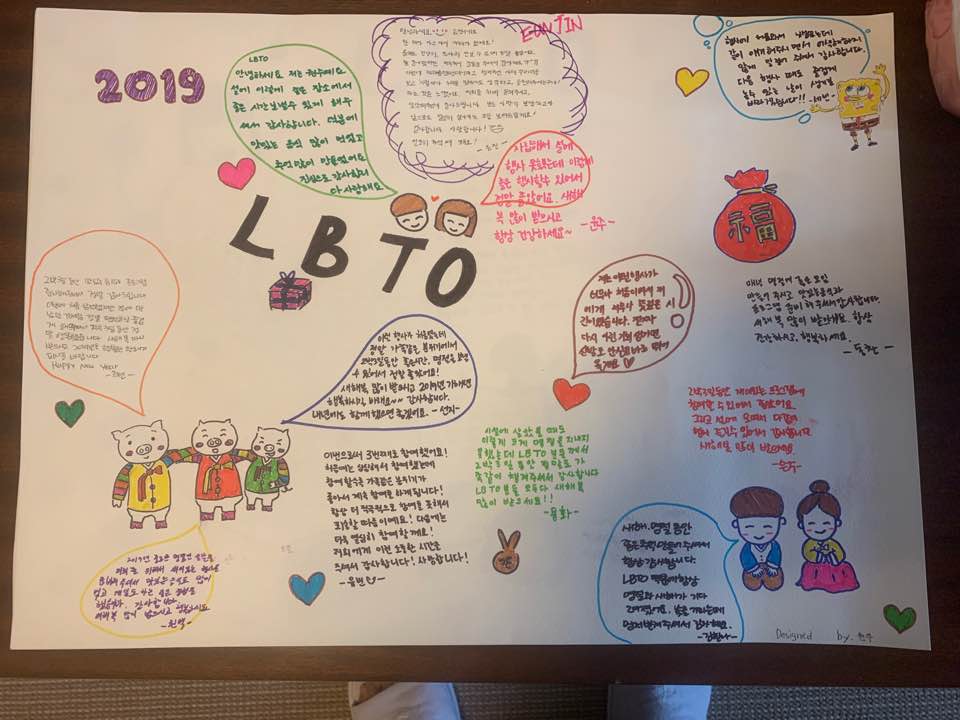

Every year for the past two years, LBTO has hosted two holiday events for aged-out orphans — Lunar New Year and Chuseok. During these two biggest holidays in Korea, families will often have a week of festivities during which no one works or goes to school.

“But these kids have no place to go,” Julie says. Often, they will just stay in their dorms.

During the holiday celebrations, Julie and Kim don’t do any lectures or seminars or counseling sessions like they normally would when the students gather. The students stay together in a nice hotel. They cook traditional foods and exchange gifts. They joke around and socialize and relax.

“I want them to feel like they are just as important,” Julie says. “They are cared for, and loved, and I want them to understand they are very special and they have a right to celebrate, just like anyone else.”

To the more than 25 aged-out orphans who attend these events, Julie and Kim have become both family and mentors. Often, Julie says, orphans in Korea hold tight to their feelings, and give answers that people want to hear when asked about their lives. But they trust Julie because she understands what it’s like growing up in an orphanage, and aging out into Korean society.

“The kids, the orphans, they’re more willing to open their hearts because they understand I understand what they are going through,” Julie says. “They do not open their hearts to most other people. But see, there is a connection because they understand that I went through the same thing they did.”

Currently, LBTO is providing monthly stipends for 11 aged-out orphans to cover needed expenses while they work to graduate college. In the two years since LBTO was founded, they have provided scholarships for a total of 14 students, two of whom have already graduated — one as recently as February 2019. One is still working to find a job, and the other one already has a job lined up. Although Julie says the government of Korea is working to reduce discrimination in hiring practices, orphans still struggle to find employment after graduation. For that reason, LBTO continues to support the program participants until they find a job.

Myung Hoon is one of the 11 students in the program who is still working toward his degree. “After I met Love Beyond the Orphanage, I allowed myself a dream and my dream was not just ‘a dream,’” he wrote in his letter. “It helped me to break my thought that orphans can’t have dreams. There are no words to express my gratitude to LBTO … you have given me not only scholarship money, a great opportunity but also confidence, motivation and a vision.”

Once he graduates from Manhattan School of Music, Myung Hoon hopes to secure a position playing viola in an orchestra in the U.S. He also hopes, he says, “to be a role model for the 1,000,000 orphans, to help show them to dream and to let them know that they deserve to dream.”

Myung Hoon does not want to return to Korea after he graduates, and Julie understands his decision.

“Here, there is no discrimination,” Julie says. “You work hard and you get treated according to how hard you work and your skills. I see why he doesn’t want to go back to Korea.”

But Julie is hopeful that in the coming years, as LBTO and other organizations raise awareness about the challenges that aged-out orphans face in Korea, life will gradually become easier for kids who have no family name.

“My greatest hope is that the whole of Korea’s perception would change so [orphans] don’t fear anyone knowing who they are,” she says. “So it’s okay for them to freely say, ‘I grew up in an orphanage and that’s totally fine.’ You know, acceptance. I want them to be accepted into society and feel free to be who they are.”

Together with Love Beyond the Orphanage, Holt International is now working to identify ways we can help prepare institutionalized children in Korea to lead successful lives once they leave their orphanage.

Learn more about Holt’s work in Korea!

See how sponsors and donors create a brighter, more hopeful future for children and families in Korea!

Can you please give me any information on the best way to find family in South Korea? My mother grew up in Do Bong Orphanage. She was lost from her family around age 7 and was never able to find them.

Hi Sarah, thank you for asking. Was your mother adopted through Holt International? If so, we could help you try to track down her birth and family records – it depends on how much information her family left with her when she entered the orphanage. For more specific information, please email our Post Adoption Services Department at [email protected], they are the birth search experts over there and will be able to help you as much as they can.