In 1993, Holt began placing children from China in loving families in the U.S. Here, our staff reflects on 20 years of international adoption and child welfare work in China — including the many Chinese adoptees who are now coming of age, graduating high school and beginning the bright futures we always hoped for them.

Every year, Jian Chen leads a group of adoptees on Holt’s annual heritage tour of China. Most of them she hasn’t seen since the day their parents took them home from China to the U.S. — since they were just babies among thousands of other babies waiting for permanent, loving families. With few exceptions, all of them are girls from China’s first generation of adoptees, placed within the first ten years. Some came home as early as 1993, the year that Holt began placing children from China. The following year, Jian joined Holt’s staff as an assistant and interpreter. She now serves as Holt’s vice president of programs in China.

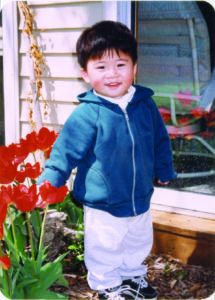

“I wanted the opportunity to bring them back,” Jian says of the children she helped find homes for in the 1990s. “To escort them back to China and see how healthy and delightful they are — how strong and positive about their life — that touches me.”

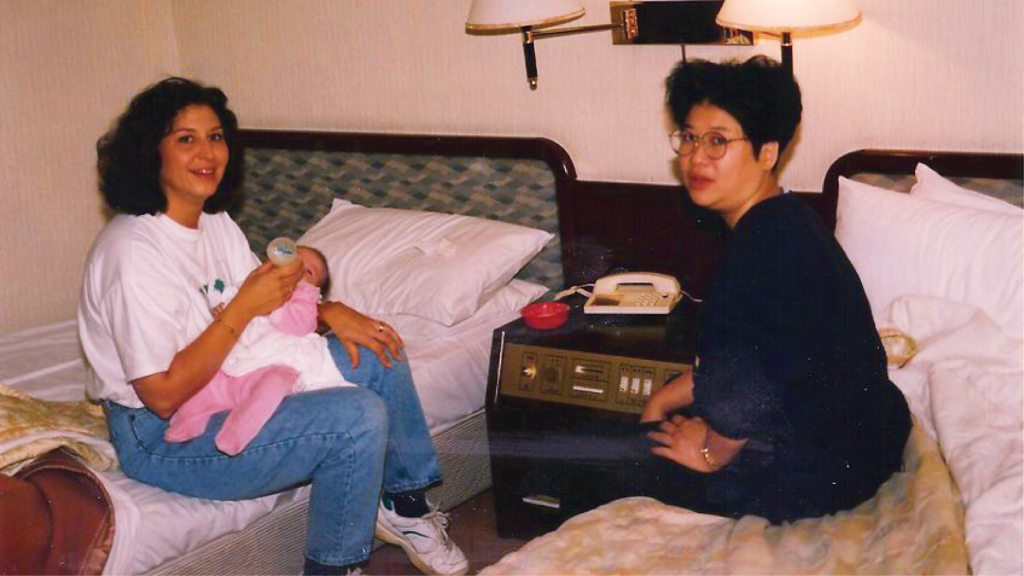

Three years ago, on the 2010 tour, Jian reunited with yet another group of girls adopted from China. As usual, Jian was struck by how radiant and full of joy they all were. But on this tour, one girl in particular stood out to Jian. Like the other girls, she was quite beautiful, with shiny black hair, high cheekbones and a lovely smile. But that’s not what struck Jian most. Although 15 years had passed since she last saw her, Jian vividly remembered this girl. She remembered that as she handed her to her mother for the first time in 1995, Jian was saddened to see several giant boils on the scalp and chin of this otherwise beautiful baby.

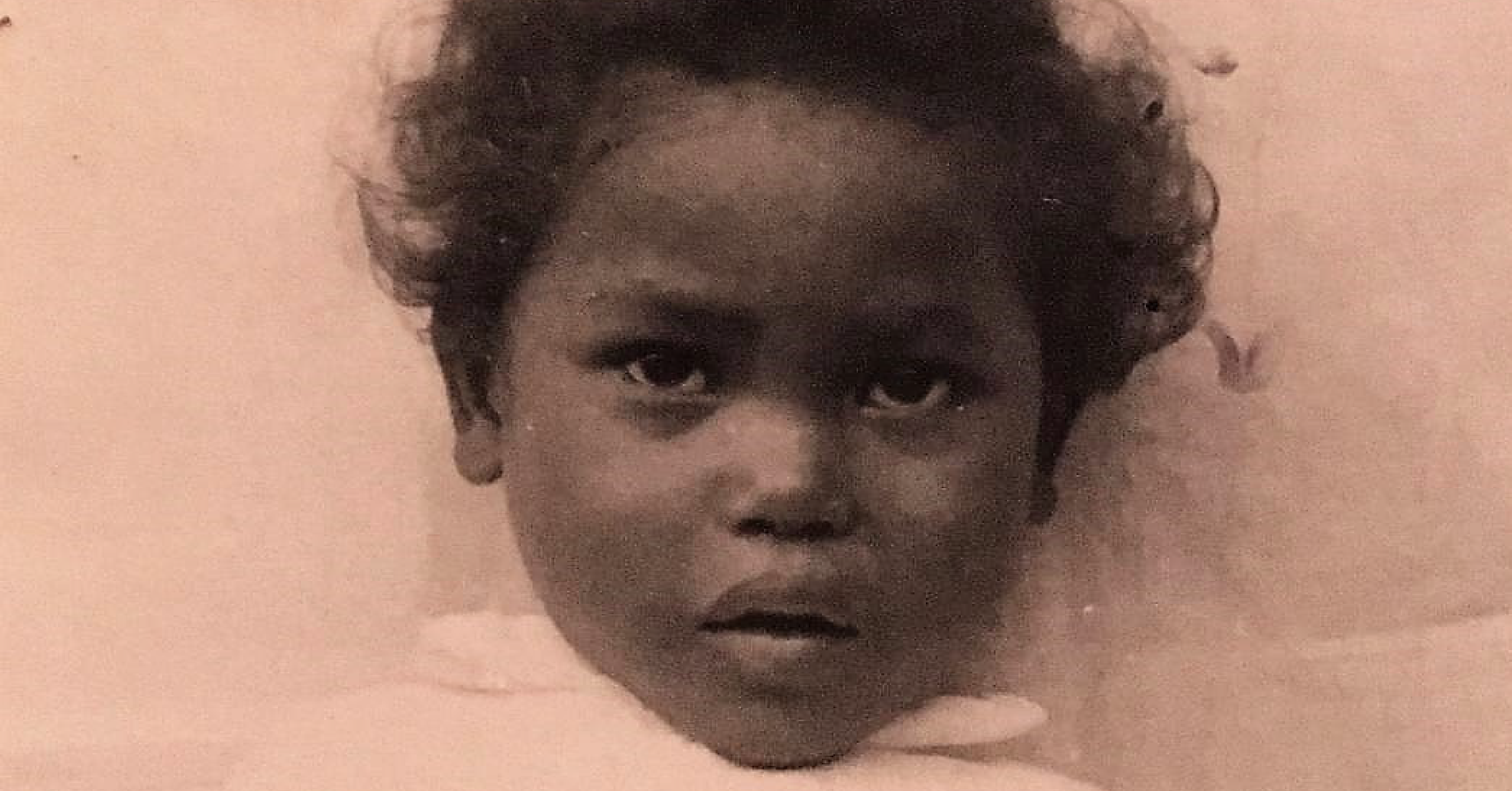

Like so many of the children Holt placed from China in the early 1990s, this girl suffered from the poor care she received in an orphanage. At the time, China was experiencing the highest rate of abandonment since the government first implemented its one-child-per-family policy in the late 1980s. Historically, families in China were very large — with a typical family having as many as ten children. “People are encouraged as a culture to have more children,” explains Jian, who grew up in the southern province of Guangxi. But as China’s population began to grow out of control, the government developed the one-child policy as a solution.

“One or two children were coming into the orphanage every day, sometimes four or five. Orphanages became overwhelmed with children, most of them infant girls laying two or three to a crib. Overcrowded and underfunded, the orphanages soon became breeding grounds for infection. Boils, skin rashes and scabies were common, and often exacerbated by malnutrition.”

Jian Chen, Holt’s vice president of programs, China

While reasonable in theory, the one-child policy had one very unfortunate and unintended consequence. Instead of having fewer children — and facing extreme consequences if they failed to comply with the policy — families abandoned children that would not in time support their family. As parents in the countryside traditionally rely on sons for retirement support, they preferred to keep children born male.

“One or two children were coming into the orphanage every day, sometimes four or five,” Jian says. Orphanages became overwhelmed with children, most of them infant girls laying two or three to a crib. Overcrowded and underfunded, the orphanages soon became breeding grounds for infection. Boils, skin rashes and scabies were common, and often exacerbated by malnutrition.

In January of 1995, when Jian first traveled with Holt, she saw for herself the child welfare crisis occurring in her native China.

At Holt, our nascent China team began feverishly recruiting families to adopt from China — often with little more information than a name and a picture of the child. “There was such a hurry to get them out,” says Jian. Many of the children were so sick and malnourished when their parents came to China to bring them home, Jian worried they might not survive. “Sometimes,” she says, “I would lay in bed at night and wonder…what if they don’t make it?”

Before Jian joined Holt’s staff in 1994, she knew very little about international adoption. After coming to the U.S. in 1986 on a college scholarship, she settled with her family in Eugene, Oregon — the small college town where, in 1956, Harry and Bertha Holt founded what has become the world’s largest international adoption and child welfare organization.

At the time that Holt began recruiting for a Chinese interpreter, Jian was busy raising her children and not interested in full-time work. But at the urging of a friend, she responded to the ad in the paper. When Holt called her to set up an interview, Jian was shocked to discover a link between this little town where she lived in the U.S. — and the small city where she grew up in China. “When I told the person on the line that I was from Nanning, he screamed!” she says. Holt’s first adoption program was in Jian’s hometown.

“I knew this city inside and out,” she says. “I knew the government officials, had all the info. I knew this was something meaningful for me.”

What Jian did not yet know, however, was how huge an impact Holt would have on the lives of thousands of children in China. To Jian, international adoption was still a foreign concept. “I didn’t know adoption. I hadn’t seen enough,” she says. Although Holt’s social workers had identified loving families who were all well equipped to parent, Jian felt exceedingly protective of the children. In the beginning, when Holt staff united children with their adoptive parents in China, she wondered if they were going to have a peaceful life in the U.S.

Despite misgivings about displacing children from their birth culture, Jian knew all too well what it feels like to be separated from your family. Jian was just 8 years old when the Cultural Revolution swept through China. To avoid the fighting in the city, her parents sent her to the countryside to stay with distant relatives. “It was painful,” she says. “That kind of feeling — of uncertainty and fear — it was carved in my bone and my heart. I don’t want any child to have that kind of feeling.”

In the decade that followed Holt’s first rush to find families for children from China, the process became much more smooth and systematic, and families throughout the world began opening their hearts — and homes — to “China’s lost girls.” Because of Holt’s history and experience with international adoption, the Chinese government sought Holt’s assistance when refining their process. “Early on, China reorganized and became a pretty efficient process,” explains Susie, who from 1995 to 2005 worked as a member of Holt’s China team. “China felt like a country really committed to finding families for kids.”

While many children found families through adoption, orphanages in China continued an ongoing struggle to care for the many more children who came into care every day. Food and other resources remained scarce, and caregivers few. But gradually, as Holt developed a stronger relationship with China’s government, our staff began allying with local officials to improve the quality of care for children living in institutions.

sitting over pots.

Early on, Holt recognized the importance of developing a solid in-country staff. “We realized it was more effective to have a local staff versus ex-pats working with the orphanages,” Susie says. “Not only did they speak the language, but it wasn’t an outsider coming in and telling them what to do.”

In 1996, Holt helped Guangzhou orphanage develop a special baby care unit where infants at risk of dying received urgent medical care. Two years later, Holt helped the orphanage in Nanchang establish their first foster care project — providing a family-like alternative for children in institutional care. In the ensuing years, Holt replicated this model for children throughout China — a model of affectionate, attentive care to nurture children’s growth and development while they wait to join permanent families. “Getting them out into the community and finding foster families to care for them was truly transformative for the children,” says Susie.

“They loved the children, and were so proud — every family,” says Holt’s director of adoption services for China, Beth Smith, of her first visit with foster families in 1999. “They provided total care for the children.”

China — ensuring they receive the nurturing attention they need to grow and thrive, and later join permanent families through adoption.

Still, Jian worried. While the quality of care improved for children in China, Jian worried about the children who had joined families in the U.S. “Like parents worry,” she says, “I worry.” Through the years, Jian had seen and interacted with many young Chinese adoptees at Holt family picnics and other gatherings. Her worst fear never came to pass; not only did they survive, they were now thriving in their families. “I saw the children are happy — always running around,” she says. But what about when they are older, she wondered. How will they feel about abandonment? How will they feel about adoption?

Between 2002 and 2006, more than 30,000 children from China joined adoptive families overseas. By this late date, news of China’s abandoned girls had become widespread among hopeful adoptive families. But during the same time period, a dramatic shift began to occur.

Due to greater family planning and compliance with the one-child policy, families began to have fewer children — causing fewer overall cases of abandonment. Meanwhile, China’s growing economy (along with high rates of infertility) helped spur a rapid growth in domestic adoption — allowing children in care the opportunity to grow up in the country and culture of their birth.

At Holt, it might have seemed as though our work in China was done. As a result of these changes, many more children either remained in the loving care of their families or joined adoptive families in China. But it soon became clear that despite a rapid decline in abandonment and growth in domestic adoption, many children remained behind — growing up without a family in one of China’s social welfare institutes.

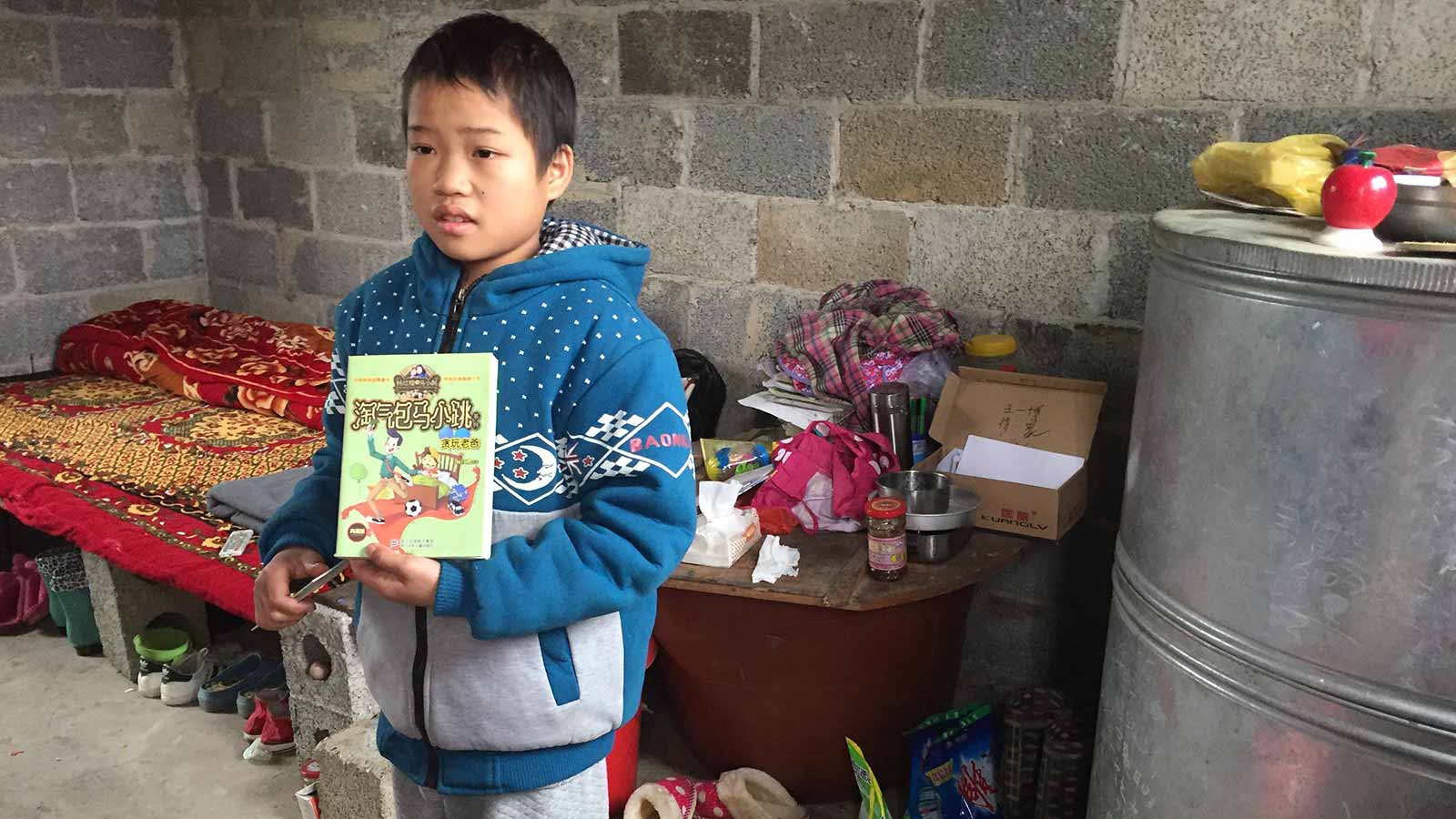

The children who now need international adoption to have a family are often older or have special medical needs, many of them minor conditions that can be managed or corrected with surgery. Ironically, many of the children now living in China’s social welfare institutes are also boys.

With increasing fervor over the past five years, families have come to embrace the changes in China adoption — welcoming children with special needs into their homes. As Beth recently wrote in an article on the changes in China adoption, “To see families shift their vision from a ‘little girl with pigtails’ to a 2-year-old boy with a cleft lip or an infant with a minor heart condition, and report back eight months later that they’re completely in love with their child, is truly amazing.”

In many ways, Holt’s China staff was uniquely equipped for the challenge of finding families for children with special needs. Since the early 1960s in Korea, Holt has made extra effort to find loving homes for children with mental, physical or developmental needs. When our programs expanded to other countries, including China, we did the same. “At Holt, we placed special needs kids from the very beginning — whenever there was an opportunity,” says Jian.

“Over 95 percent of the children were healthy girls,” Beth says, “but there were always a few with special needs.” Today, Holt places hundreds of children with special needs from China every year.

As our adoption program has evolved to meet the needs of children with special needs, so has our child welfare work shifted to care for children now in greatest need of support — children living in poverty outside of China’s social welfare system.

Looking back, Holt’s China team is proud of the work they have accomplished over the past 20 years. Many of the programs Holt staff developed have had a tremendous impact on homeless and vulnerable children, and today serve as models for other child welfare organizations working in China. But the focus will always be on the children who still need our help. “Group homes and foster care are working,” Jian says, “but China still has a long way to go in caring for children.”

As our adoption program has evolved to meet the needs of children with special needs, so has our child welfare work shifted to care for children now in greatest need of support — children living in poverty outside of China’s social welfare system. “That’s the group of children we are reaching out to now because there are fewer children in the orphanage, and government support for the orphanages is so much stronger,” Jian says. For these children, Holt provides educational support to help them reach their full potential — as well as resources needed to remain in the loving care of their birth families.

Jian may never stop worrying about children in need in China. But 20 years after she first tentatively placed a child in her adoptive mother’s arms, Jian no longer worries about whether that was the right decision. She feels absolutely confident that adoption was the best solution for that first generation of Chinese adoptees, as well as those placed in the years since. Every time she meets another vibrant group of adoptees on a heritage tour, or looks through the graduate issue of the Holt magazine, she grows more and more certain. “They may have issues down the road,” she says, “but now I know, their adoption was very positive.”

Beautifully written..I am one of those who adopted in the year 2000 with Holt .

Which was one of the best experiences.

I have a beautiful 21 year old daughter from Hunan province. She has been the light of my life.

She has blossomed into the most beautiful, brilliant , caring,self confident woman.

Mia will graduate from Embry Riddle Aeronautical University in the fall with a 4.0 GPA average in aeronautical science.

Words can not express how grateful I am to be her Mom.

I recognize that Ming Yuan Hotel console! Holt had a wonderful staff to help us in 1995 —Les W., Craig S. and family, Xiao Xiao, Matthew, and Christine at Mother’s Love. My children are now 27, 24, 23 and 21. I always enjoy learning more about the early days of Chinese adoption.

Thank you for this synopsis of Holt’s work in China. I will share it without daughters, adopted in 1997 and 2000 in Nanning. They both benefited greatly from foster care.

As the mom of 2 girls adopted in China, I was disappointed by this article, which seemed to revive the “savior” narrative and to ignore the perspective of the adoptee. It’s possible to celebrate the new families formed through adoption, while at the same time acknowledging the loss and trauma that is a big part of the story for many adoptees. My family has been benefited greatly from Holt’s post-adoption counseling services here in Illinois–services which are based on a very different understanding of the adoption journey than was reflected in the article, and which empower adoptees to better understand and shape their own story. It would have been great to hear some adoptee voices in the article.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts, Nancy. While this historical piece is valuable in that it shares historical information and insight from Holt team members who helped create our adoption and family strengthening work in China, you are right that it fails to acknowledge the trauma and loss inherent in adoption and does not include the perspective of Adoptees. In the eight years since we produced this piece, we have learned and evolved a lot in our approach to the adoption narrative, with greater inclusion of Adoptee voices and perspectives. And we agree that Adoptee voices would have strengthened this piece significantly. We have added a note at the end and a link to some of our content that shares Adoptee perspectives on the adoption experience. Thank you again, and we’re so glad that your experience thus far with Holt has been one that empowers Adoptees to shape their own stories.