With the support of child sponsors, one brave group of women in Cambodia seek a better life for their children.

They call themselves the Brave Women.

Sitting in a circle on a large, green tarp under the shade of cashew nut trees, many of the women sit with their legs bent under them to one side, calves parallel, in the way so natural to Cambodians. It’s bright and hot, and little clouds of dust rise under the fidgeting feet of the children lingering to watch. Some women hold smaller children on their laps. Nearby, two large, cream-colored oxen graze on dry brush, their ears and tails swishing at flies.

The leader of this group is an older woman with strong hands and a small streak of gray hair near each of her temples. She speaks softly, but confidently in Khmer. “We call ourselves the brave women because everyone has to be brave and speak up,” she says.

“We call ourselves the brave women because everyone has to be brave and speak up.”

Her explanation of the name draws a nervous laughter, as if the idea of brave women is a laughable concept.

But, it’s true. Given Cambodia’s recent history, the act of gathering together as a group of women is nothing short of brave.

A History of Holt’s Work in Cambodia

From 1975-1979, more than one in four Cambodians were killed or died during the genocidal revolution orchestrated by Cambodia’s communist party, the Khmer Rouge. When the Khmer Rouge seized national power, Cambodians had already endured years of secretive, U.S.-led airstrikes that killed more than 600,000 people against the backdrop of the Vietnam War.

But the revolution just brought more violence.

Within days of taking over the government, Khmer Rouge leaders forced everyone to join ranks. Families were separated. Schools, hospitals and historical landmarks destroyed. Buddhist places of teaching, pagodas, were turned into prisons and interrogation centers. Many people starved or died of hunger-related disease. Tens of thousands of people were unjustly arrested, tortured and forced to confess treason. Cambodians were encouraged to denounce their peers. And entire families were killed without ever understanding what they had done wrong.

There is no way to overstate the destruction of the Khmer Rouge. In four years, more than 2 million people died — and those who survived were left to deal with the aftermath. Today, Cambodia still struggles to recover, and very few victims of the Khmer Rouge have received justice. But the Khmer Rouge didn’t just kill people. By forcing villagers to turn on each other, the brutal regime destroyed entire social structures. Community support became a foreign concept. People grew afraid to work together to solve common problems. And that fear remains today.

But the Khmer Rouge didn’t just kill people. By forcing villagers to turn on each other, the brutal regime destroyed entire social structures. Community support became a foreign concept. People grew afraid to work together to solve common problems. And that fear remains today.

Today, more than half of the population is younger than 22. Pervasive poverty continues to threaten the safety of children and families. National education systems are lacking. Access to quality healthcare is weak. Economic opportunity abysmal.

Holt began working intermittently in Cambodia in 1991. In recent years, we’ve bolstered our programs that aim to strengthen families vulnerable to separation. We partnered with local NGO Cambodian Organization for Child Development (COCD) in 2013 and Children and Life Association (CLA) in 2015. Together with our on-the-ground partners and child sponsors in the United States, we seek to protect children from trafficking and exploitation, increase educational opportunities and keep at-risk families together by holistically addressing their needs.

When we began working in Cambodia, one of the first problems we recognized as a threat to children was the strong individualism among villagers.

Together with our on-the-ground partners and child sponsors in the United States, we seek to protect children from trafficking and exploitation, increase educational opportunities and keep at-risk families together by holistically addressing their needs.

Buth, the director of CLA, says that during the Khmer Rouge, the elite exploited the close-knit nature of communities to enslave the peasant class and force them to work for the revolution. As a result, people opted to work individually to protect their rights. Even today, villages are afraid to trust one another — a fear that makes it easier for traffickers to prey on children and more difficult for families to sustain a profitable business. When families fear working together, the whole community suffers. Children suffer.

“There’s no collaboration in the villages,” Buth says. “So when families face trials, they don’t know what to do or where to turn. They may take out a high-interest loan to pay for healthcare.”

To begin repairing trust among villagers, Holt helped form community groups in every village where we work, open to the mothers or grandmothers of children in child sponsorship. These groups empower women by teaching sustainable agriculture and income-generating skills, creating a community-based savings and loan program, and by teaching women how to work together to solve problems and keep their children safe.

Soon after, the Brave Women were born.

How Sponsors Support Women & Children

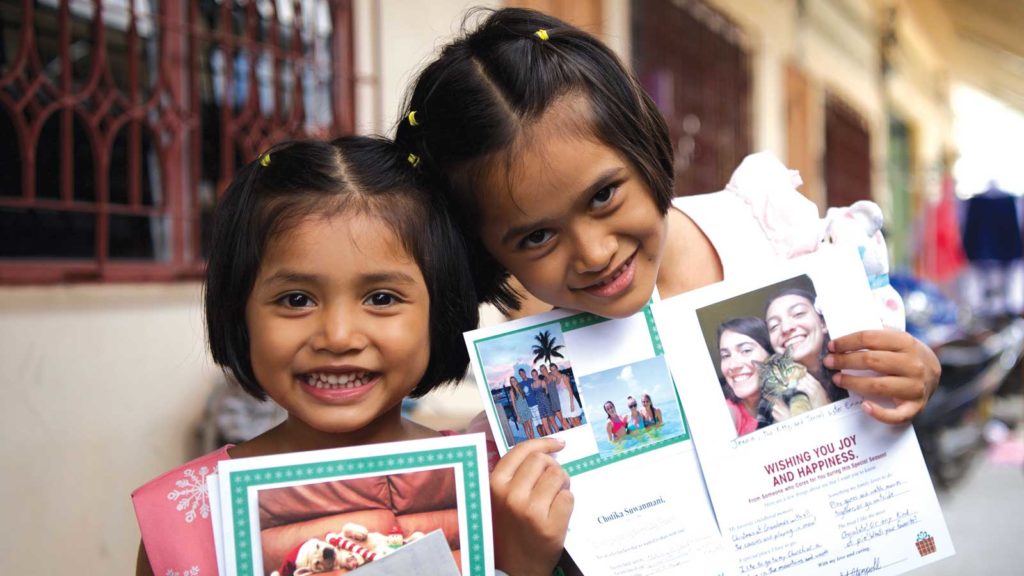

They started with 15 members, but the Brave Women have doubled in less than two years. Each month, 30 women meet to discuss common hardships, share wisdom about child and animal raising, and add a small amount of money to their savings and loan account.

Holt’s on-the-ground partners visit frequently, and share information about keeping children in school, preventing child trafficking and reporting abuse. They provide trainings to help the women improve rice yield and host workshops about topics like composting or vaccinating baby chicks. Holt-sponsored children often attend, too, just to play with friends or watch what their mothers or grandmothers are learning.

With some initial capital provided by Holt child sponsors and monthly deposits and interest payments from every member, the women have an account with nearly $2,000 they can borrow from in small increments of $100-$300.

Borrowers repay their loan through weekly payments, with 2-percent interest. With their loans, the women are able to cover emergency medical expenses, pay off other high-interest loans or invest in income-generating agricultural activities.

One of the Brave Women opened a repair shop for tractors with her husband. Saywen, a 29-year-old mother of two sponsored children, expanded her small grocery stall, and now she stays home with her children while her husband travels for construction jobs.

“I always dreamed of owning a shop like this,” Saywen says. “I never went to school. I can’t read or write. My son started school late, so he is only in the first grade, but I hope all my children can stay in school.”

“I always dreamed of owning a shop like this. I never went to school. I can’t read or write. My son started school late, so he is only in the first grade, but I hope all my children can stay in school.”

Saywen, a member of the Brave Women

Once Saywen pays off her first $100 loan, she wants to borrow again and add an electricity source and small refrigerator to her shop so she can keep produce fresh longer and sell cold items.

“The poor feel hopeless, excluded and discriminated against,” says Pola Ung, the young founder and CEO of COCD. “At self-help groups, they feel confident and strong.”

One Mother’s Story

Phanny is 35 years old and the mother of four children under the age of 11. A member of the Brave Women, she’s easy to recognize by her warm, dimpled smile and thick, shiny black hair.

Phanny lives just a few hundred yards along a dusty path from where the Brave Women meet each month. Her house is built on low stilts with walls made of tightly thatched bamboo or scrap wood planks.

In front of the home is a clay water pot as tall as Phanny’s waist with a tray of fish resting across the rim. Behind Phanny’s home is a stall where four pudgy pigs lounge about, sleepily oinking at each other.

Phanny begins cutting up a watermelon to share, a smile spreading across her face.

“She looks so happy,” says Kosal, Holt’s director of programs in Cambodia, smiling with satisfaction. “It’s a big change from the last time I saw her a couple of years ago.”

The indicators of wealth in Cambodia are usually visible, tangible items — tin roofs instead of thatch, electric lights, pumped water versus open pit, access to irrigation instead of reliance on rain.

“For families who have lived 40 years without a savings account, a cow is life-changing. It gives hope.”

Pola Ung, founder and CEO of Cambodian Organization for Child Development

Animals are like bank accounts, since they cost a considerable amount to purchase, but they also generate large amounts of wealth and food security. The larger the animal, the more wealth it can generate for a family. Chickens produce eggs, which families can eat and sell. Baby chicks grow into chickens and can be sold for about $5 each. Piglets can be sold for $20 each about 20 days after they are born. Cows produce fertilizer and can help reduce the labor of growing rice — the main source of food for all families in Cambodia.

“For families who have lived 40 years without a savings account, a cow is life-changing,” Pola says. “It gives hope.”

The savings and loan aspect of the women’s self-help groups is critical — and so successful that mothers of children in Holt’s child sponsorship programs around the world often receive similar support. For around $100, women are able to purchase several hens or a pair of piglets. This investment, while large for the families Holt works with, can pay off big. The animals will eventually produce offspring, generating income that families can use to access medical care or medications or to pay school fees — keeping children from dropping out at a young age.

For very successful families, animal raising and farming can be their primary source of income, and even generate enough income to cover “additional” costs like children’s school books and uniforms, which Holt child sponsors usually provide through their monthly gifts. More importantly, having the ability to generate income and care for their family gives parents hope for the future—hope that they pass on to their children.

“Before, we didn’t know how to improve our position,” the Brave Women’s leader says. “To get a loan is very efficient now. Before, we only had bad options.”

Two years ago, life was bleak for Phanny and her children. Phanny’s husband left for work one day and never came back. Her only way to make money was by selling traditional Khmer medicine, which she would make from plants, leaves and other foraged ingredients. She would sell her medicines to neighbors and make less than $1 per day.

Her children were undersized. She worried how she would feed them enough. They were often sick, but she could not afford a doctor. And without funds to purchase required school supplies, Phanny wondered how long it would be before one would have to drop out.

But, when the Brave Women formed, their fate changed.

Phanny passes out chunks of watermelon, even sharing with a group of older, neighborhood girls lounging on her front step. Phanny recently learned how to compost during a COCD training, and she proudly shows off her compost pile.

So far, Phanny has taken three small loans, all of which she’s repaid. She purchased two pigs with her first $125. After she repaid her first debt, she borrowed again to buy five chickens and a rooster. Now, it’s hard to count the number of hens strutting around the dusty yard, some with a small flock of baby chicks in tow. With her third loan, she purchased some items to sell for profit — like the fish drying on her water pot. Soon after, she sold some of her chickens to buy another piglet.

Now, Phanny’s income is enough to meet the needs of her family. Their hygiene is better, Phanny says, even though they don’t have access to running water or electricity. Phanny says she’s learned many skills, and she feels more confident that she can care for her children and encourage them in their studies.

Encouraging Sponsored Children to Dream

Like most Cambodian children, Phanny’s three sons and youngest child, a 4-year-old little girl, are a bit shy and modest. Cambodian children are taught to be humble, polite and quiet, so they often hide their smiles or avoid doing anything to draw attention to themselves. The boys are wearing the school uniforms that were purchased for them by their sponsors — black pants and a white, collared shirt for boys, calf-length black skirts for girls. Every student in the country wears this same uniform, regardless of province or age — a small nod to the communist history.

The three eldest children attend a school about a mile away, a distance they walk with their mother or classmates each morning. Many of the children in their classes are also sponsored through Holt.

“I like social studies, arithmetic, playing ball and skipping rope,” Phanny’s oldest son, a sixth grader, says. “My sister wants to go, too, but she’s too young.”

The fact that he can so easily discuss what he likes about school is a good sign.

“Before, kids were hopeless about the future. No one asked them what they wanted to be. Now they have to think about it. They know it’s important.”

Buth, director of Holt partner Children and Life Association

Even today, discussing collective issues in a public setting remains brave — especially for women. But, while conceptually new, gatherings like the women’s groups are actively reversing one of the most long-standing outcomes of the Khmer Rouge regime — the crushed ability to dream of a better future.

This changing legacy is especially important for children. When we ask children or parents simple questions about their future, they seem perplexed. Children have never been asked, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” No parent has ever responded to the question, “What do you dream about for your children?”

When we pose these questions to the Brave Women and their children, a whispering murmur breaks out among the women. Kosal fills the quiet. “They haven’t been asked this,” she says, “so they are just realizing this must be a very important question.”

The women’s answers are similar to what you might hear anywhere. Both children and parents hope that kids will grow up to be doctors, teachers or policemen. Many children say they hope to work for an NGO like Holt, which shows the meaningful impact Holt sponsors have had on the lives of children in this community.

Pola asks another question to the women, unprepared for the depth of their answer. “Will you let men join?”

“There’s no need,” the leader says. “We can do it.”

The women laugh, but not apologetically. They laugh in agreement, with confidence not only that they can learn new skills and provide for their families, but that they already are.

Billie Loewen | Former Holt Team Member

Become a Child Sponsor

Connect with a child. Provide for their needs. Share your heart for $43 per month.

I want to help and visit some villages.

thanks for sharing!!